Book Nook

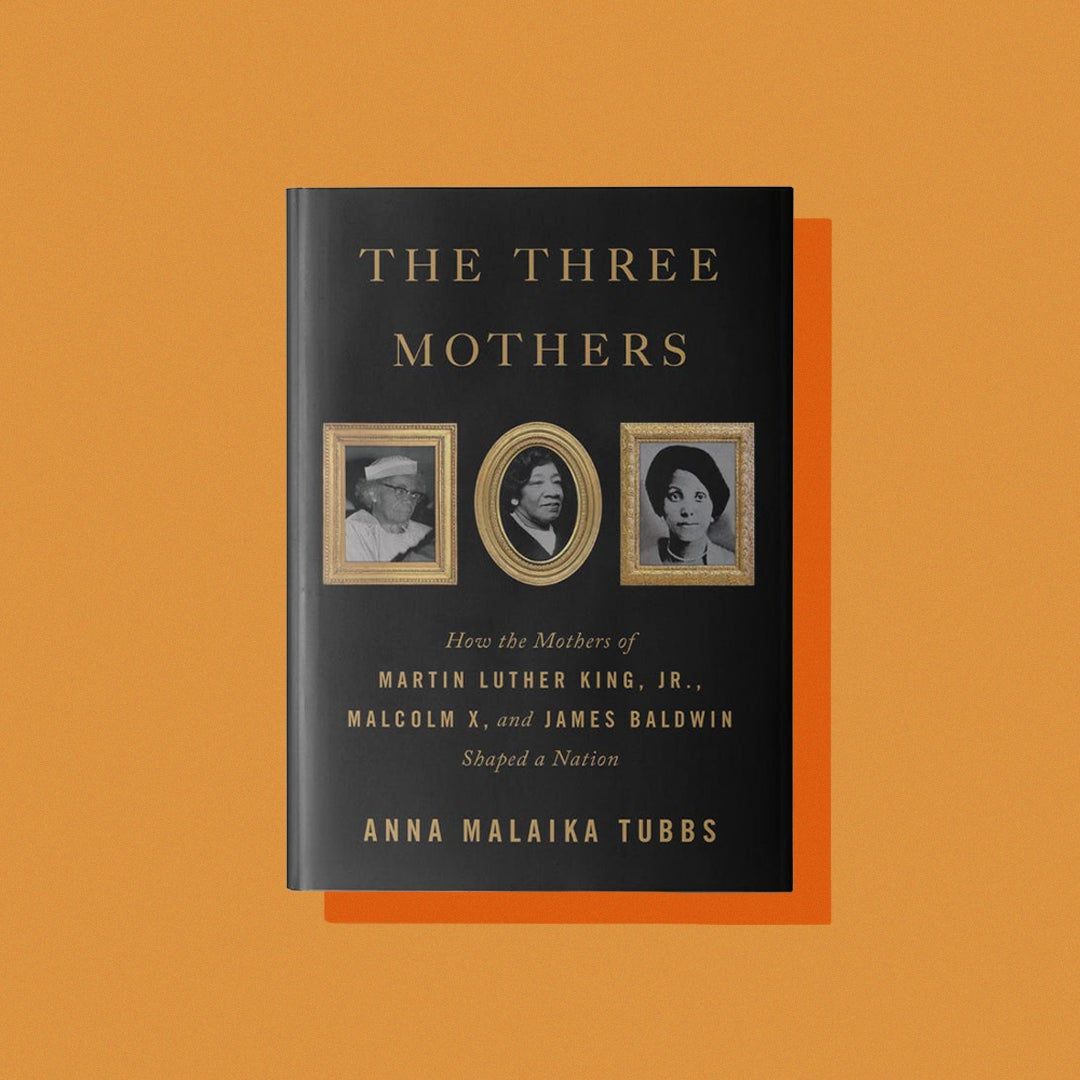

Anna Malaika Tubbs on The Three Mothers

- Interview By

- Liz McDaniel

What was it like to delve into the stories of these extraordinary Black mothers just as you were becoming one yourself?

It was such an incredible experience. I was already very interested in honoring mothers before I was expecting my son. My mom always made a case to say how important mothers are in society and how we have to focus on women’s issues and mothers issues and that’s how communities thrive and do well. She always presented examples of places where if women were being taken care of, if there were protections in place, if parenthood was something that was respected, then overall that society would do really well. So when I started my PhD knowing I was going to do something to contribute to fighting the erasure of Black women’s stories, I remembered my mom saying this and I thought, Okay, I’m going to do something around motherhood, Black motherhood and fighting erasure, so that’s how it all came together. But then, in the middle of it, to find myself expecting, it added a layer of depth where I felt even more connected to the women. But I also became very cognizant of how sad it was that a lot of the fears that I felt, becoming a mom, becoming the mother of a Black child, were still so connected to the issues that Alberta, Berdis and Louise had faced. It opened my eyes to the need to speak up and have a book that was both personal as well as political and informative as well as something that could be healing and bring more people together.

You write “Black parenthood—specifically Black motherhood—is both awe-inspiring and extremely vulnerable” and can you relate that to your experience and how you felt when you first learned you were pregnant?

As somebody who has studied Black women and their history and of course being a Black woman myself, but also being very well informed of the attacks that are waged against us in terms of dehumanizing treatment, I knew from the beginning that I would be more likely to experience bias when I was seeking care for me and my child. There’s all these studies that show how different it is for Black women, so that vulnerability was something that I immediately thought, I need to do something, I need to make sure my agency is respected, that I’m treated with respect and dignity, and that’s why in learning more about Alberta, Berdis and Louise, I realized they were never three women who said, We have to accept things as they are. They were aware of what was around them and all of the issues and instead said, We’re going to challenge these, we’re going to change the systems around us, we’re going to make sure that our children know their worth and know their value and know that they are loved even if their country doesn’t always treat them that way, we’re going to be a part of that change. So that was really inspiring for me and one of the reasons that I sought doulas to work with to have women of color beside me throughout the whole process and while I was in labor and even beyond and just really recognizing that I wasn’t going to accept anything as if it was unchangeable.

You took special care in your book to paint a picture of these women’s lives before they became mothers as well...can you talk about why that was so important and how you personally have experienced that identify shift of becoming a mother?

I think it’s crucial. Because one of the things that I think a lot of moms feel is that they’re erased somehow. I think that’s a universal theme for all mothers, not only Black mothers, that our identity is erased once we have children. You become “Mother of…” which actually should be a title of honor but because of the way we treat motherhood in the United States, it feels like this kind of second class citizenship. So I knew I was going to highlight their lives before to help people understand that they were important even if they never had these famous sons. That they were contributing to the freedom fight, that they were activists in their own right, that everything they learned as young women translated into their identities as mothers. It wasn’t like the person was invented when she became a mother but instead it was she decided to become a mother it was a growth in her identity. I think that’s also important for modern readers to not feel like our identity has been erased. The second layer of that is of course I’m honored to be my son’s mother. I’m honored when people say, Oh, you’re Malakai’s mother, because I see motherhood as this influential, powerful role. I’m aware that things can’t happen without me and I walk through the world with that kind of confidence in my motherhood. So as long as we can start getting more people to see motherhood in that light then it’s okay if somebody wants to claim that as a part of my identity, while also acknowledging that I didn’t become a person when I became a mother. And for all women that decided not to become mothers they are equally important in this world. It’s just an ongoing political discussion around how we treat women, how we treat the role of mothers.

You have talked about how there’s this tendency to acknowledge the influence of a father but diminish the role of the mother. Can you tell us more about that?

Yes, “Father of” is a title of honor, but “Mother of” feels like, Oh yeah, you’re just the mom. It’s shocking and it’s infuriating and truly when we tell more stories about what mothers have done for their children, and how mothers’ identities before they were mothers translated into who their children became—and we can see that so clearly in Alberta, Berdis and Louise—then we just have a much more realistic picture.

You write about the differences between these women so clearly, but what do you think is the most important thing that the three mothers had in common?

The diversity is something that I cared deeply about because Black women are so often put into categories and reduced in terms of who we are. We are a very unique and nuanced and diverse group, but there are definitely similarities between the women’s stories. Some of them are quite painful because despite where they were from, what family they were raised by, what resources they had, in many ways they were treated very similarly and faced these very traumatic moments because they were Black women living in the United States. In other ways, the similarities were incredibly inspiring. One that I always think of and it’s something that I think about in raising my children, is that all of the mothers wanted their kids to be well aware of what was happening in the world. They weren’t trying to protect them from the truth of how ugly the world would be beyond their homes. So you have these moments in the book where they’re all having conversations with their kids about what might happen. They’re thinking about racism, they’re speaking very specifically about violence outside of their home, but they also clearly emphasized that their kids could be a part of changing that. Whether that’s through getting their education or through participating in marches and rallies alongside their own family members or the way in which they taught them at home through books about their history and their family history and these family meals where they’re discussing what’s happening in the world around them. So it’s this balance of informing our children that yes, this world is not fair, as a Black child, these are things you’re going to face, but also it not being something that defines them. And I struggle with that sometimes because it puts a lot of pressure on our shoulders as Black mothers and Black children to be in some way in charge of helping the world. But in other ways we don’t really have a choice. So how I reconcile that is also knowing that we’re part of a much larger team, and part of a larger legacy, so that also allows us time to feel joy and to just be a family and to relax and not have to constantly be thinking about the change that we’re going to inspire but to know that we can change things. I think as long as those many different layers are thought about and considered it’s a really powerful tool for mothering.

Was there a moment that stopped you in your tracks in your research?

When I found that little paragraph where one of James Baldwins’ principles says that he clearly inherited his writing talent from his mother. It’s so beautiful! And this is his career. This is what we know him for. And so for the people around him to know so clearly that she’s the one that taught him how to write was so beautiful and I’ll never forget that.

Can you tell us about your own mother and the best advice she ever gave you?

She was born in Clarkston, Washington. Her name is Nancy. Her dad was a judge and her mom was this very traditional, but very smart stay at home mom and my mom was the youngest of her family. So all of these things were important because she in many ways was told these are the traditional notions of what it means to be a woman. You need to become a mother. You need to know how to cook and clean. Even if you’re associated with these powerful men, it’s not power you’re going to inherit. You’re going to need to become a wife and a mother, etc. She always had her eyes set on the law, but over and over again was told that’s not something that women do. Even her father, who was a judge, said, This isn’t for you. And so all of that translated into how she mothered us. I can see it so clearly. I obviously didn’t learn all of these things about her past until pretty recently but I’m now so aware of why it mattered deeply to her when she said things to us like, You should always question those who are in authority and never be afraid to be curious. Our parents both wanted us to have a very international experience. They took jobs anywhere they could to teach the law at different universities but just said if a new offer comes up in a new country we’re going to go. Everywhere she really emphasized this notion of one, learning things for ourselves, not taking that kind of privilege for granted of being able to see the world for ourselves but also encouraging us to always ask questions of the systems in place and again to never assume that they were stagnant, that everything could always change.

How has the way that you were mothered come through in how you mother?

My son is only 18 months old but anything that he wants to try out or think about or be curious about, I do my best to not limit him at this very early stage. If he’s making a mess with something or whatever in his mind he’s creating something new and I’m not going to be the one to limit him because the world will do that plenty. So I’ll say, I guess we’re painting on the ground, that’s cool. I try to encourage that curiosity as much as my mom did because I think it’s the most important lesson out of the many that she taught us. I just don’t ever feel limited because she taught us to feel that we were unlimited.

You do such a good job of telling these three women's stories against the backdrop of their era...how do you see your experience in this current moment as compared to theirs?

It almost makes you cringe how similar a lot of the conversations still are and how difficult it is to relate on a certain level to what Alberta, Berdis and Louise were experiencing during Jim Crow. Of course they’re different things, less explicit maybe sometimes, but other times not really, like what just happened with two Black children very publicly being killed by police. So it’s definitely something that I’m well aware of. It’s very scary, but I’m an optimist and I’m hopeful. Focusing on these women's stories allows me to be even more of the optimist that I am because their awareness of what was going on around them is what allowed their children to be aware of what could change. And the way they weaved their faith in with their vision for the future and what’s always possible is something that I really keep my eyes on because I definitely think that’s something Alberta, Berdis, and Louise did beautifully. They really encouraged their kids to find their own paths in that fight. Even their kids that aren’t as famous. Almost all of them found a way to contribute to something larger than themselves and I find that to be really beautiful and inspiring.